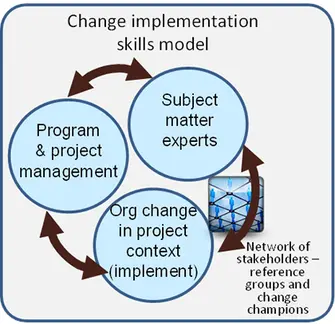

The key to successfully implementing change is to have the right people, with the right combination of knowledge, skills and experience, in the right roles. The following model is one I have used successfully when considering the resourcing of implementation project leadership groups and project teams.

This fundamental mix needs to be in place for every change project.

Large, complex and/or transformational change projects should have a leadership team that incorporates each of these specialist professions through the use of multiple, experienced leaders working collaboratively together.

For smaller, simpler projects, a single leader can cover all elements even if they are not highly experienced in each, as long as the fundamental skills and specific areas of focus are each covered off through team members within the project.

(And how to avoid being involved in a failure)

When I first started in the world of projects and management consulting, I had some amazing mentors, and some of their advice comes to the front of my mind when I consider each new project. There are all types of statistics for different types of projects and industries, but I think these fundamentals underpin any project.

The primary advice was “You never want to be involved in a failed project – you’re only as good as your last project.”

“Obvious” I hear you say. True, but it is still good advice to keep at the front of mind before you commit to a project in any way. The important answers are to the question “How can you predict if a project will succeed or fail before you commit?” This is where the true wisdom and experience lies. So here are some elements I look out for – I’m sure there are others to consider also.

What executives with mature project environments know

Almost every procurement process sets selection criteria, with “value for money” as one of multiple criteria. The greatest misconception is that the cheapest price or cheapest daily rate represents the best value for money – that couldn’t be further from the truth. A level of experience and a mature project environment is needed to truly consider value for money. I have worked with organisations and staff who really understood the concept, and I have worked with those who did not. It isn’t until things go “off the rails” that the concept becomes clear, and generally it is too late to make budget or change contracts by that stage. Experience is so valuable when applied to selections and procurements – getting it right up front can save a lot of time and cost when it comes to timely delivery and in potential future disputes and recovery.

Factors to consider in assessing value for money

The factors to consider in a value for money assessment will be specific to the particular product or service you are looking to acquire. It is worthwhile listing out key elements that are important to your organisation and the specific change, before starting or as part of tender assessments. They should always be revisited during the tender assessment process, because often I learn about new developments and capabilities that represent excellent value through a tender process. So here are my suggestions of factors to consider in assessing value for money:

What’s the difference and what do you need?

There are many definitions of project management available to describe the profession and the elements involved in managing projects. What is really important for timely and successful project delivery is getting the right people in the right roles for each specific project and program.

Mature project organisations and executives with a good track record of project accountability use the following complementary roles in different combinations to achieve good project outcomes cost effectively. Some effective combinations used in practice are illustrated on the following page.

- Project Director

- Project Manager

- Project Coordinator or Project Officer

- Program Director

- Program Coordinator or Program Officer

What’s the difference?

Each organisation has a different scope of projects and programs to manage in their portfolio, and therefore different structural requirements for management and support. Methodologies and publications provide great guidance and definitions to support organisation and role considerations. The more programs and projects you have running, the more relevant you will find the organisational arrangements recommended in methodologies. When there is only one program or few projects and programs, in practice it can be a little confusing.

Program Director

The Managing Successful Programs methodology describes the role of the program manager as being “responsible for leading and managing the setting up of the program through to delivery of the new capabilities and realisation of benefits. They have primary responsibility for successful delivery of the new capabilities and establishing governance.” Taking an integrated and holistic view across all projects is critical for strategic alignment and to mitigate duplication and gaps. It mitigates the risk of impacted stakeholders being inefficiently and haphazardly bombarded by each project.

Is bigger really better when it comes to your portfolio of programs and projects?

In our fast paced world, change is constant, it needs to be constant and improvements need to happen quickly. Customer expectations are constantly changing, and technology is evolving so quickly, opening up new possibilities, and generating new customer expectations. This means that operational improvement initiatives are constantly being identified and initiated, and the more significant, costly and risky changes need to be structured into projects and programs for effective management.

So how much is enough? How much is too much? How to strike the balance?

Balance is the key. An important element of portfolio management is to provide guidance and governance for starting, continuing and ceasing change initiatives across operations and programs of projects. It is about making sure an organisation gets the best “bang for its’ buck” in terms of scarce funding and change capacity available and focusses on the right initiatives at the right time. There are key elements to consider for the right size portfolio of the right initiatives for your organisation at a point in time. Often bigger is not better – but it all depends on the context.

My top 10 practical tips

For many years on projects I didn’t use the term “change management” or “organisational change management” to describe any project activities. I found that language to be a major barrier to acceptance of the types of activities required on a project to transition to a new way of doing things.

I have always found that the need for communication and training was well accepted, but in practice, these alone will not result in the impacted staff being motivated to change or well prepared to do their day to day activities efficiently and effectively in the new way. Most people understand and accept that getting people to change is very difficult, and usually is the fundamental difference between project success and project failure. Many projects write theoretical papers, strategies and approaches, but skim over the practical activities that could really help impacted staff.

So how do I get around the barriers where people bristle at the term “change management” and want to cut those costs from the project? I use terms like “business preparation” and “business readiness”, as project managers, sponsors and executives accept these as critical elements of a project. Those who think that change management is a “nice to have” but a waste of money and just all too much “fluff” can accept that the business needs to prepare for the new way of operating.

Practical learnings and tips

For the well-accepted methods, frameworks, theories and other practical tips, I recommend you read some of the many books and web sites on the subject of organisational change management. Following are my practical observations and learnings about what will help get a lot more people to come across to the new way – it is a “fluff-free” zone.